Ever since I was able to get the NBN I have been using Aussie Broadband as my Retail Service Provider. In Australia, the internet is usually delivered by the National Broadband Network. The NBN is the wholesale provider of a mixture of technologies, including VDSL, (both as Fibre-to-the-Node and Fibre-to-the-Curb), HFC and Fibre-t0-the-Premises.

Before I was with Aussie, my ISP of choice was the [Internet; it was the darling of the Technical propeller heads. It had many widely respected employees who could have their heritage traced back to the beginning of the internet within Australia. They also took the responsibility of driving the Australian knowledge of IPv6, offering it initially via a tunnel broker, then over GRE and finally natively using DHCPv6 over PPPoE.

Internode was also the driving force in ADSL2+ being released in Australia, as the incumbent telco Telstra stated at the time that ADSL2(+) was unsuitable for Australian conditions. Internode initially took them to task offering via shared lines (Telstra phone and internode ADSL2+), and then as a naked service via Telstra's Unconditioned Local Loop Service (ULLS).

Unfortunately, the NBN announcement caused the ISP market to contract, and Internode was sold to another of Australia's original ISPs, iiNet. They continued to operate Internode as a separate entity whilst merging their backends. Unfortunately, and much to the disgust of the community of nerds on Whirlpool Forums, iiNet sold out the TPG, a cheap, oversubscribed network.

Aussie Broadband was the result of the amalgamation of Wideband Networks Pty Ltd and Westvic Broadband Pty Ltd, both of which had been trading since 20o3; with the merger completed in 2008. They gained a good reputation in the areas that they served in Victoria, South Australia and the Northern Territory.

When they started to offer NBN services, they were against unlimited plans. They gained a reputation as providing well-priced plans with a performant network, as the leechers were not interested as they didn't have unlimited. Thus, they started to see the people who were using Internode beginning to migrate towards their networks.

Their CTO also engaged with the Whirlpool community often taking requests for routing changes well past most people's bed times. Their network expanded, and they looked after it. They also worked out how to take care of the NBN’s Connectivity Virtual Circuit issue. This is probably the most controversial part of the NBN.

RSPs are charged two charges for each connection, an

- AVC - the bandwidth from the NBN core towards the Access Seeker (customer)

- CVC - the bandwidth from the NBN core towards the RSP.

When the NBN was designed initially, the idea was that the NBN would transport all NBN traffic from the customer's ACG to a Point of Interconnect where the RSP would take over transporting the traffic; there would have been a couple of POI in each capital city for redundancy. However, the ACCC changed this idea and decided that there should be 121 points of presence as the fibre carriers saw the NBN transiting traffic as them taking over what they should be doing.

The ACCC decided that if there were more POI, that would mean that small providers could offer services only to their locale, however, this has not been the case, as most traffic is carried by the big 4 (Telstra, Optus, TPG and Aussie Broadband). With the NBN now not backhauling traffic from the AVC to the capital cities, this means that the ISPs then had to purchase fibre links off one of the big 3. However, the NBN did not reduce or remove the CVC.

This caused ISPs to oversubscribe their CVC, thus causing slow speeds and packet loss; this has only recently, at the time of writing, been announced to have been removed on higher rate (100/40, 250/25 and 1000/50) plans.

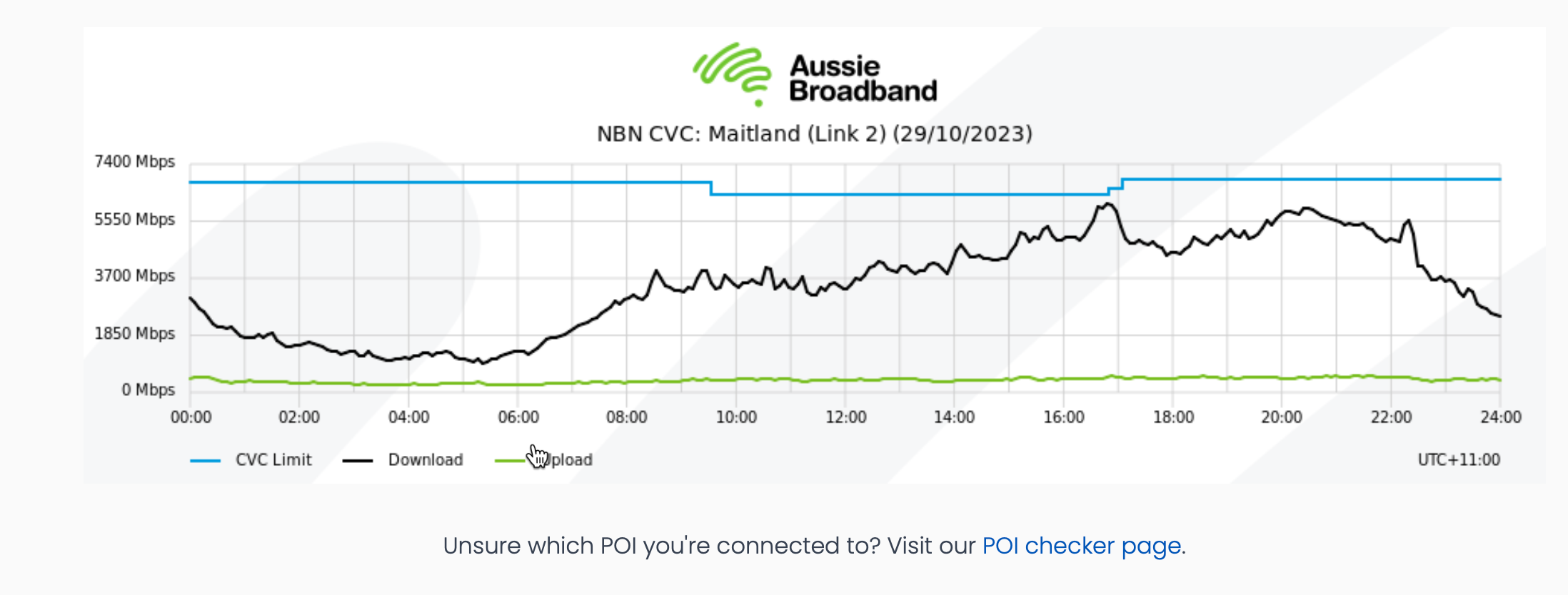

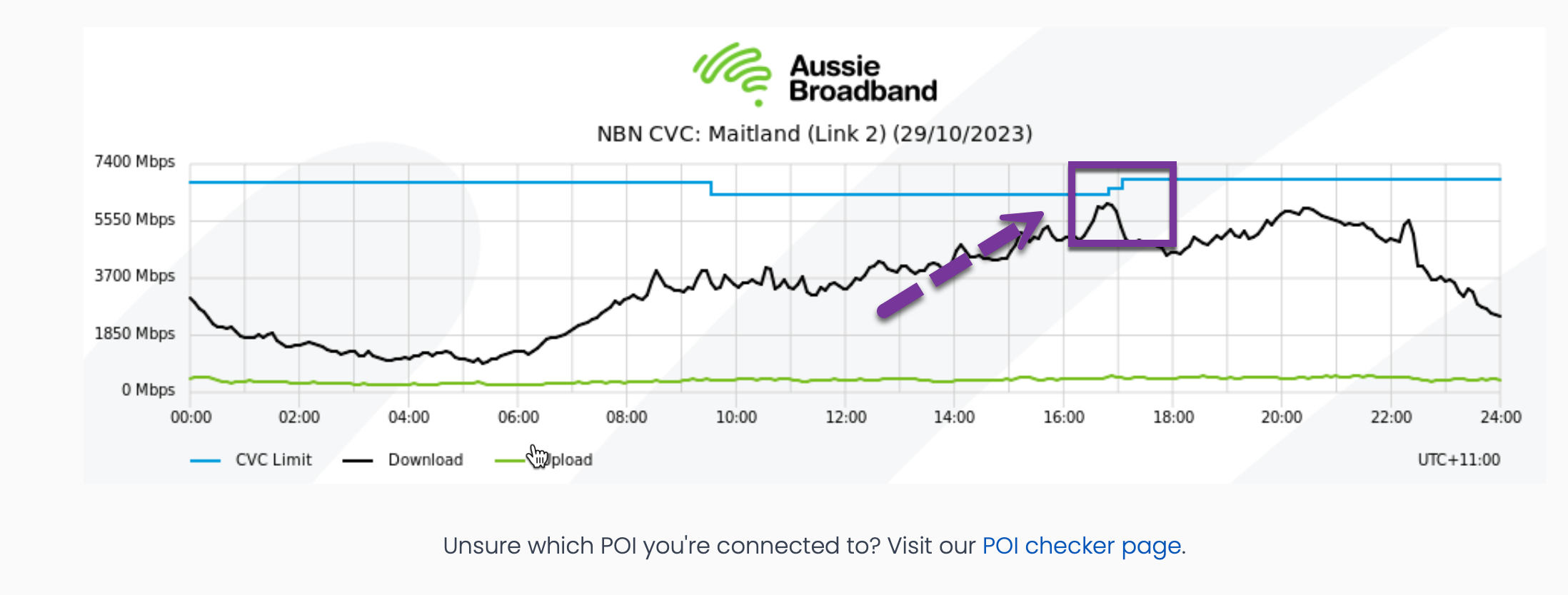

To get around this issue, ABB created the CVC Bot; its job was simple: it knew what the traffic profile was on a CVC link, and it would scale up the CVC and peak night demand occurred and then backed it off as the demand subsided. Aussie took great delight in permitting its users and potential customers to have a look at what the

In 2020, Aussie BB released a prospectus and floated on the ASX. This was the beginning of the end of their stellar performance. This allowed ABB to have their fibre delivered to every POI, thus improving this portion of the network; as they were now a public company, you could see them tightening the screws down on overheads.

But it was still bearable, as John Bot and Whirlpool were active on the network. Last year, John hung up his boots and moved on to greener pastures. Nobody picked up the presence on Whirlpool, and you could tell that the free overhead managed by the CVC bot was reduced, probably to reduce overhead. The below image shows how close the CVC is and how it does not react as it used to.

Aussie Broadband was not the cheapest provider; it was a solid performer that cost a little more than the rest, but I was not too bothered with the cost, as I just wanted my network to perform when I wanted to use it. This was no longer the case; instead of getting the 800mbit/s during peak, it would drop to the low 600s. At this point, the dollars that I was throwing at them did not stack up, so I went searching for another provider.

Searching through the Whirlpool forums, I was reminded of Future Broadband. I had seen them before, and their product had interested me, but I was turned off because they used the TPG network, and so I stuck with ABB.

I went back and found them, and their product was very interesting. They use layer 3 AAPT (TPG Business ISP), rather than TPG's retail business. This had me hooked. The AAPT network is business-based, and as such, their peak periods are during central business hours, and even during these times, I can pull 700-800mbit/s during business hours.

Even though I had a "static IP" with ABB, it was not a statically routed IP and relied on DHCP and DHCPv6 to assign the IP addresses to my service. In the last 12 months, there have been an increasing number of outages where their DHCP infrastructure failed. It also meant that even if the service failed, the router would think that the connection was still up, as it wouldn’t fail over as it had a default route supplied by DHCP and had not timed out.

With Future Broadband, the IP and IPv6 ranges are statically routed to me with an IPv4 /30 and IPv6 /126. This means that the Internet is available as soon as my router is booted, and I don't have to wait for authentication and DHCP to do its stuff.

The pricing of the product is also very sharp. I have a static IP (ABB charged $5 per month for this), which is ridiculous, as once my internet is connected, it will have an IP address assigned to it, and it will be used unless I disconnect. Future Broadband was $140 compared to $155 with static IP. But as I said, this is also an AAPT service called IP Line, which is the same TC-4 NBN link they would provide to a business customer requesting this connection.

But if you want to save additional money, Future Broadband allows you to pay 6 months in advance and will provide you with a 10% discount. This drops the price for my internet down to a super sharp $126, which is about the same price as the cheapest shitty NBN RSP.

Overall, I am delighted with my choice, and as long as the network remains a good performer (which with AAPT, I am sure will happen), I will remain a customer.